Malcolm Parker

USC News & Media Seminar

The same organization responsible for the management of the Los Angeles River made a decision that supporters of the river say will halt its revitalization.

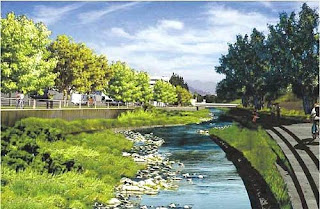

The LA River was deemed on June 5 as being “non-navigable” by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers because of the instability and lack of depth of the rivers water. This decision makes environmental groups like Friends of the Los Angeles River (FoLAR), FarmLab, as well as the city of Los Angeles feel restricted from revitalizing the river. Apart of getting the river recognition as being a “navigable” source is making the river a more traditional and appealing one, legally and physically. And environmentalists say this requires that some concrete be removed not from the river’s banks but its riverbed.

Groups like FoLAR desire to take the concrete out of its riverbed “to revitalize wetlands and create more green open spaces,” said Alicia Katano FoLAR’s educational programs director. Katano believes that, “Increasing our wetland/green space areas will improve our capacity to capture rain water and replenish our aquifers as well as replenish a much needed natural habitat for riparian plants, birds, insects and fish as well as create green open space for people as well.”

If this process is not carefully handled, it poses severe problems for the rivers future and its “navigability”--the river’s flood control capacity could be placed in disarray, engineers fear.

“The impact could be severe in terms of water quality,” LA City Public Works Commissioner Paula Daniels said. “Concrete removal will bring erosion, which produces silt,” she continued.

“Too much silt makes waters murky…less sunlight impacts oxygen levels in the water which will affect aquatic life and plants,” said Katano.

Silt and the LA River have a history too. Much silt contaminated the river when it was utilized as a drinkable water source in 1800s due to railroad construction.

Silt appears to be posing problems for the river’s recreational future too. People still fish at the Long Beach Harbor, although the cleanliness of the fish caught there is unknown. Most of the fish found are carp, indicators of an unhealthy ecosystem ridden with hazardous sediment.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which finds the river an “untraditional, non-navigable water source”, is currently undergoing a study of how much concrete removal is suitable. Corps’ concerns are about the silt wearing away the concrete side channel of the river, not the riverbed.

“We must maintain flood control capacity if concrete removal is to happen,” LA City council member Jill Soural said.

Revitalization and concrete removal from the riverbed may be achievable for environmentalists if they clearly outline their goals to Corps of Engineers. FoLAR’s Katano said that, “the silt that concrete removal would produce would only be a serious problem if we want the river’s water to be a drinkable water source.”

And according to environmentalists, potable water is not the plan at all. “I’m not sure the L.A. River will ever become a direct source for drinkable water for our city. However, the L.A. River could help lessen the amount of potable water we buy to water our lawns, wash our cars, and by providing an alternate source of water for our non-drinking purposes.” she continued.

Environmentalists do not stand alone on this issue; the Mayor of Long Beach, Bob Foster, praises the goals river’s revitalization. The Long Beach Harbor would be one of the places for concrete removal.

“Because the Long Beach Harbor is the mouth of the Los Angeles River, we inherit its flaws, so we are absolutely on board with creating green spaces by any means possible,” said Bob Foster’s Legislative Aid, Taylor Honrath.

“It deserves our best efforts to restore its water quality, habitat and adjacent wetlands. We work closely with other government agencies--notably the City of Los Angeles--business interests and environmental groups such as FoLAR to determine how to restore the river without compromising its ability to keep our communities safe from flooding. Removing portions of the cement lining is a very promising proposal with many environmental benefits and worthy of continued consideration," said Stephen Cain, executive of the California Environmental Protection Agency and the Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board.

“The City is working with the County and the Corps to examine ways that we can upstream water storage and treatment so that in the future, river water will be cleaner and it will be possible to remove concrete from the channel in order to expand its potential for having ecological value as habitat and open space. I do think that concrete removal is a viable option if we are able to provide the necessary upstream water to transfer some of the flood control capacity that currently exists within the River channel now into its upstream watershed,” Carol Armstrong, Ph.D., project manager Los Angeles’s Bureau of Engineering.

The Los Angeles city government just received a $25-million federal authorization that includes money for an ecosystem restoration study of the LA River undertaken by the Corps of Engineers determine the status of the river. Until then, the concrete stays put. As the Los Angeles Times stated, “There are indeed competing notions of restoration. The river is 51 miles long--and lined with as much possibility as concrete."

g the

g the